The significance of plant cell walls

The outermost layer of the plant cell, the cell wall confers the cell’s shape and size, and provides defence against herbivores, pathogens and physical damage. Some cell walls are strong and in some cases stiff (e.g. those of wood; cell walls hold trees up!), but other walls are highly flexible, e.g. the primary wall that surrounds a rapidly growing cell. Different cells have very different walls — they range in thickness from about 0.07 to 10 µm, and the walls of different cell-types have different compositions.

Its position as the outermost layer of the cell allows the wall to serve several important roles, including

|

| Cell expansion par excellence in Amaryllis peduncle |

- ➩ dictating the shape of the cell (direction of growth)

- ➩ dictating the size of the cell (rate of growth )

- ➩ preventing the ingress of phytopathogensproviding the strength of mechanical tissues e.g. fibres

- ➩ adsorbing, and thus harmlessly sequestering, certain toxic metal ions from the soil

- ➩ gluing cells to their neighbours within a tissue (via the middle lamella)

- ➩ production of signals (oligosaccharins — see below) that can move from cell to cell, acting as chemical messages.

The plant cell wall is proving to be an exciting source of novel glycans and enzymes which may have diverse agricultural and biotechnological applications. A review article describing cell-wall enzymes and their action in vivo is freely available from J. Exp. Bot. 64: 3519-3550, 2013. The Edinburgh Cell Wall Group studies the primary cell wall as a metabolically active and structurally significant compartment of the plant cell. Knowledge of the structure and function of plant cell walls is valuable not only as a contribution towards our fundamental understanding of how plants 'work', but also as a the basis of commercial attempts to predict and manipulate the growth, morphogenesis, disease resistance and digestibility of plants, the abscission of leaves and the ripening of fruit.

|

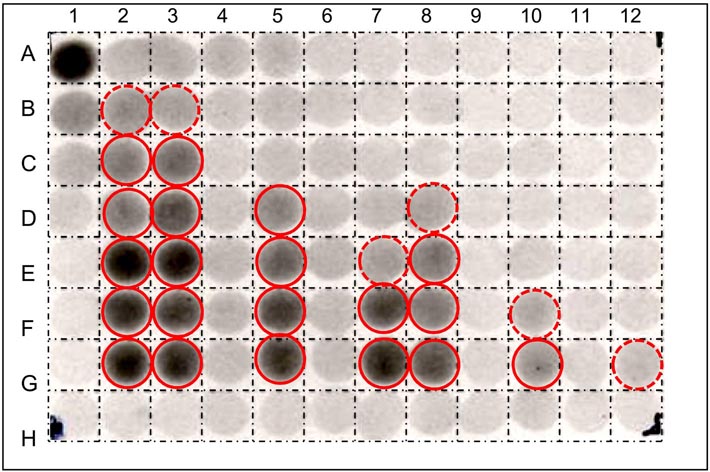

| High-throughput screens for β-mannosidase inhibitors |

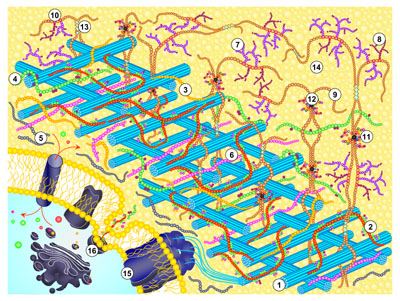

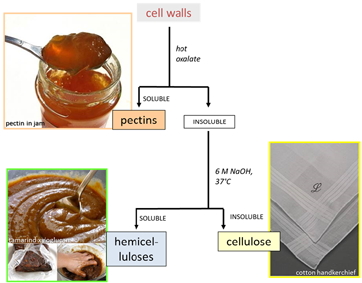

We are engaged in devising simple new assays for cell-wall enzymes and for substances that modulate the action of such enzymes. Many of these assays are 'high-throughput', can be carried out with minimal investment in apparatus, and offer scope in surveying diverse plant species and in searching for specific inhibitors of wall enzymes. Such inhibitors are potential future herbicides as well as tools for exploring the working of the cell wall. From a structural perspective, the physical properties of the primary wall govern the shape, size and growth rate of the plant cell as well as determining the plant's resistance to microbial digestion. The primary wall and its associated middle lamella dictate the texture and strength of the tissue. It is an over-simplification to describe the plant cell wall as a 'cellulose cell wall', for, although cellulose is the best known component, this usually constitutes only 25-40% of the wall's dry weight; the other 60-75% (the 'matrix' components) consists mainly of more complex polysaccharides (pectins and hemicelluloses) and smaller amounts of structural glycoproteins. In the walls of certain specialised cells, other polymers such as lignin, cutin and suberin, are important. A summary of the composition and molecular architecture of the cell wall is freely available at doi: 10.1002/9781444391015.ch1. The diagram below illustrates cell wall architecture schematically.

|

|

| Diagram illustrating cell wall architecture - click on the picture to enlarge | Simple scheme for the fractionation of cell-wall polysaccharides - click on the picture to enlarge |

From an evolutionary perspective, our studies show that major events in plant evolution were often accompanied by remarkable changes in cell wall chemistry, indicating a special role for cell wall modification in adapting plants to their altered lifestyles in newly colonised environments. The Edinburgh Cell Wall Group is exploring the changes in cell wall composition that have occurred during the progression of plant life from charophytic algae through bryophytes, lycopodiophytes and ferns, to seeds plants.

Of great metabolic and therefore biological interest is the presence in the primary wall of enzymes and low-molecular weight substrates. Wall polysaccharides and glycoproteins are synthesised by the protoplast and released to the outside of the plasma membrane, where they are subjected to numerous modifications, including transglycosylation, covalent cross-linking, hydrolysis, oxidative coupling, and the making/breaking of hydrogen-bonds. These processes result both in (a) new polymers becoming integrated into the wall material and (b) existing wall material being 'tightened' and 'loosened', with important consequences for the ability of the cell to expand (grow). Partial self-digestion of the wall generates small fragments (oligosaccharides), some of which ('oligosaccharins') are hormone-like signalling molecules. The apoplast (aqueous solution which permeates the cell wall) also contains metabolites such as ascorbate (vitamin C) and hydrogen peroxide: these are important in generating free radicals such as the highly reactive hydroxyl radical (•OH), which may play a role in non-enzymic wall 'loosening'.

|

|

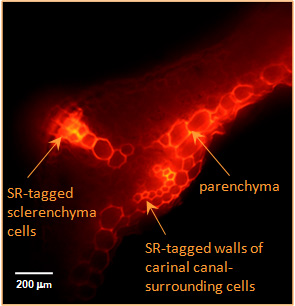

| Xyloglucan endotrans-glycosylase activity detected in the elongation zone of a root with the use of a fluorescent substrate. Root tip is at the bottom - photo: K Vissenberg 2003 | In-situ visualisation of XET and MXE action in Equisetum fluviatileae leaf - photo: L Franková 2011 |

A major experimental emphasis in the research strategy employed by the Edinburgh Cell Wall Group is to monitor the action of cell wall-related enzymes in the living cell. Our objective is to observe the in-vivo action of an enzyme (i.e., to demonstrate that the catalysed reaction actually occurs, in the wall of a living cell) by monitoring the behaviour of the substrates - endogenous whenever possible. We distinguish action from activity, the latter being an enzymological term describing the ability of an enzyme to catalyse its reaction when provided (often artificially) with substrates, at optimal concentrations, usually in vitro. Enzyme 'activity' is measured in picokatals (picomoles of product formed per second), and is usually not the same as 'action' - for example because the exact cellular compartment in which the enzyme is located may not contain optimal (or any!) substrate concentrations, the substrate (e.g. a polysaccharide, within the cell wall) may be shielded from the enzyme, a natural inhibitor or competing substrate may be present, a vital co-factor may be absent, or the pH may be wrong, etc. To circumvent these problems and to measure enzyme action, our lab therefore makes frequent use of the feeding to living cells of radioactively or fluorescently labelled precursors, and of monitoring the behaviour of metabolites in vivo. In cases where fluorescent substrates are used, this approach can reveal the exact location of a particular enzyme's action - as illustrated by the fluerescence microscopy images left .